Travel writers sure can sure muck up the world. Often, after planting a flag in some obscure territory (obscure to them anyway), they tart up slim experience with a flash of style and a dash of homework. Then—clueless as Columbus—they spin impressions into facts and accidents into discoveries. Among Balkan travelers, Rebecca West’s 1,200-page opus Black Lamb and Grey Falcon may have its literary merits, but accuracy and humility aren’t among them. And oversold conclusions can do real harm, as when Robert Kaplan’s Balkan Ghosts paralyzed US policymakers in the 1990s by conjuring the specter of “ancient hatreds” driving “inevitable” conflicts in a disintegrating Yugoslavia.[1]

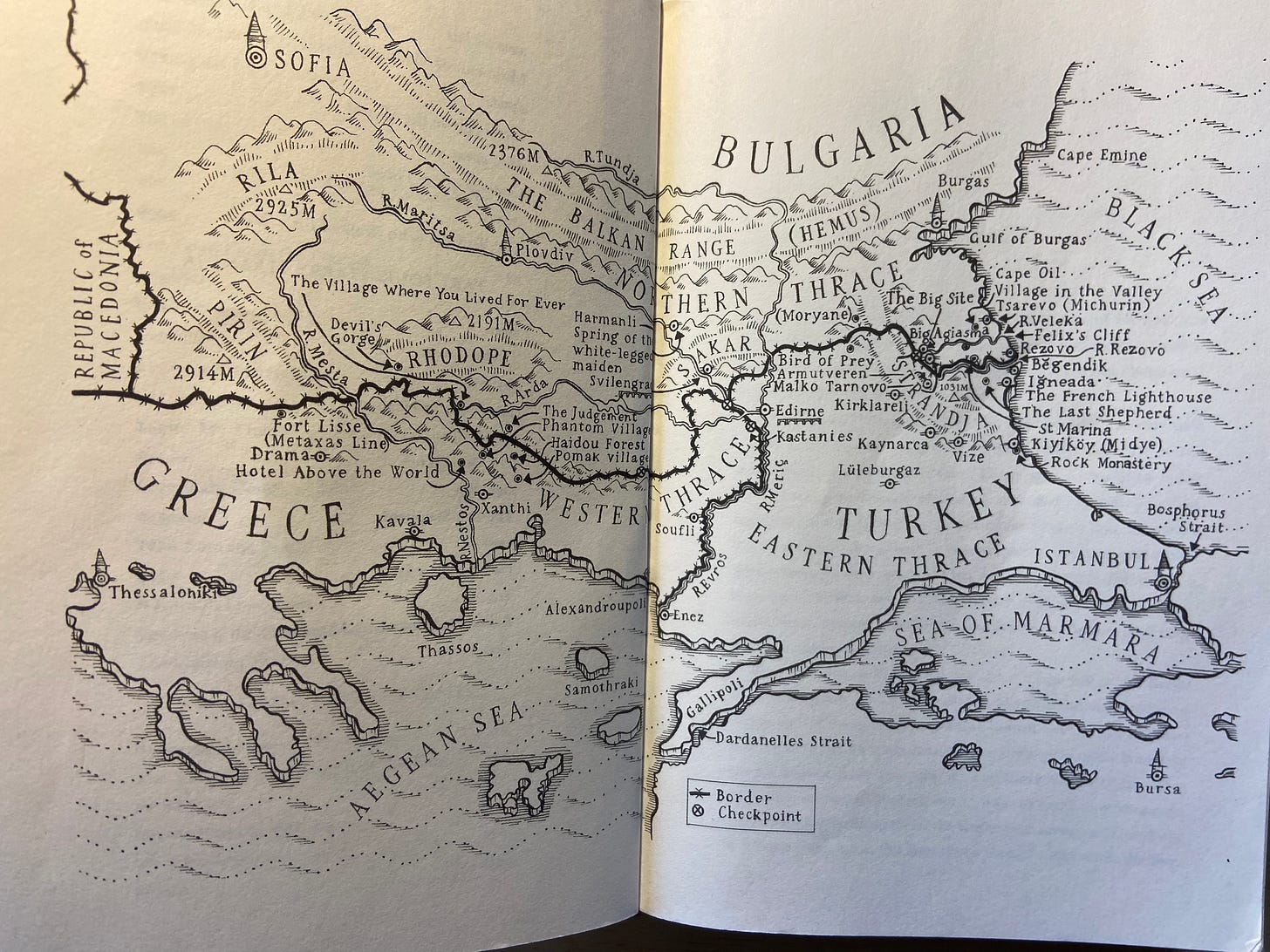

Good travel books then, occasion celebration; great ones, rapture. Which brings me breathlessly to Kapka Kassabova’s Border: A Journey to the Edge of Europe (Graywolf Press, 2017). In nearly 400 pages of lovingly woven narrative, the author takes us through the remote reaches of southeastern Europe, where the Balkans stretching toward Asia are cut by the borders of Greece, Turkey, and her native Bulgaria.

“For me,” Kassabova has said, “places are faces,” and Border is a sympathetic and closely rendered gallery of unlikely people navigating unlikely and often tragic circumstances. Their stories—conditioned by politics, economics and ethnic difference—echo deep in history’s well. The circumstances of a region where continents, cultures, and regimes have collided and mingled are unique, as are the myths, customs, and memories preserved in the backwoods. But, however particular, through them she explores forces that prove universal—the obtuse brutality of governments, the violence of racism, the destruction of wilderness, the precariousness of human life, and the hidden sources of strength available if we only look.

Learning about them, there, we learn much about us, here.

Kassabova and her family emigrated when she was a teen to New Zealand, and she found her adult home in the Scottish Highlands. In 2014 she decided to revisit the Black Sea coast of Bulgaria to see where they had vacationed back in Communist times and shared the beach with families and Soviet bloc VIPS on the “Red Riviera.” Some beachgoers back then, it turns out, were gearing up for a desperate sea swim to Turkey, a NATO country. Many never made it: border guards under strict orders saw to it that the Riviera actually ran red. The lush hills nearby bristled with barbed wire and ordnance.

At age 40 she returned to this once-forbidding place an award-winning novelist, memoirist and poet, little guessing how much her personal and literary trajectory was about to change. “I had set out to investigate the Cold War, having grown up in an open-air prison,” she recently told a conference audience, “but I didn’t imagine I would end up being fascinated by a mountain ecosystem, the border theme, the mountainous way of life, and the intricate weave of nature and culture.” Over the decade since, that fascination has spurred a quartet of books highlighting what her website describes as the region’s “rich human and natural ecosystems scarred by trauma.”

Within these ecosystems, stories of buried treasure abound: gold left by the ancient Thracians, hoards cached by refugees in various eras, dynamite stashed by hajduks (anti-Ottoman guerrillas), or goods confiscated by andarte fighters in the Greek Civil War. Abounding, too, are the inevitable treasure hunters. Kassabova counts herself as one, albeit she is in pursuit of precious meanings to be revealed in language, lore, and myth, and in the uncovering of obscure lives.

From her we learn about Nazim the Syrian refugee, Ziko the kindly smuggler, a Romani man named Tako (the “monk of happiness”) who guards a monastery and lives on nearly nothing with complete contentment. This is the merest sample. Chapter by chapter she sketches out characters who enlarge our understanding of what a life can be. They are unforgettable, at least until the next one comes along. By book’s end they blur together like figures in a once-vivid dream.

These people carry history’s burden. Their family stories go back to the Ottoman era and its collapse in the Balkan Wars of 1912 to 1914, World War One, and the displacement and persecution that followed. In the 1920s in a treaty-sanctioned process of ethnic cleansing euphemized as “population exchange,” whole communities of Greeks and Armenians were driven from what became Turkey, Muslims and Turkish speakers were exiled from Greece and Bulgaria, and Greeks and Bulgarians were swapped across fresh borders. It was a tragic time when, in one of Kassabova’s many memorable phrases, “millions lost a homeland or worse, and gained an empty house in a foreign country with the kitchen pots still warm.”

And the century was just getting going. We see the scars left on lives by World War Two, the Holocaust, and most prominently the Cold War. Today a border often figures as a barrier to keep surges of migrants out. But in Kassabova’s childhood Bulgaria’s was fortified to pen people in. “The border of this book has a half a century of Cold War hardness, she writes. “It was deadly and it remains prickly to this day.”

In those years, the forest paths were death traps and we hear about people shot and people who shot them. Some fleeing the Soviet bloc were cruelly tricked by government maps that misplaced the borders; one man who rejoiced with a picnic having reached freedom turns out to be still in Bulgaria, his celebration ended by deadly gunfire.

“The border of this book has a half a century of Cold War hardness. It was deadly and it remains prickly to this day.”

We also learn about those who made it across, once or many times. On the Greek side a guide takes Kassabova deep into the forest to a grove of beech trees where every other trunk is etched with initials and dates bearing witness to long-ago flights. The scratchings date back at least to the 1940s. One, from 1997, spelled out the name ZORA. Kassabova actually meets this Zora decades later in, as she says, “one of the freakish serendipities that seemed to shape this journey.”

Zora tells her she first crossed into Greece in her twenties, during the 1990s, a time of extreme poverty in Bulgaria. She succeeded on her fourth attempt after escaping sex trafficking, being caught and sent back, and walking for a week, starving, and drinking water from cows’ hoof prints. After marrying and then becoming a widow at 40, she lived alone at the top end of a village in the mountains. Hearing the story of this “woman who walked for a week,” we think of all the names on all those trees, the told and untold crossings. And we remember that this book is dedicated to “Those who didn’t make it across, then and now.”

“Seeing them like this, walking across the hills with nothing left in the world, we understand what our ancestors went through. And you wonder: when will it end?”

Societies erect internal borders as well, and Kassabova shows deep empathy for minority populations. She calls the persecution of Bulgaria’s Turkish communities between 1986 and 1989 “the last cretinous crime of twilight totalitarianism.” Under the Communist regime, the Pomaks, Bulgarian-speaking Muslims, were forced to take Bulgarian sounding names and faced theft, arrests, forced relocations, beatings, even murder. While many sought refuge in Turkey, others remain today, often isolated in remote villages. Kassabova returns to these Pomak communities and their healing practices in her third Balkan book, Elixir.

In our era, the desperation at the border lies mostly with Syrians, Afghans, and others crossing in the other direction, north and west to Europe. She meets these refugees– exhausted, stalled, and nearly hopeless–just over the Turkish border in Edirne in a café that is a hub for smuggling (a Rick’s Café for our time). We hear of separated families and the inevitable swindlers who take their life savings. For a resident on the other side, high up in a remote Bulgarian village, their trials stir deep echoes. “Seeing them like this,” he says, “walking across the hills with nothing left in the world, we understand what our ancestors went through. And you wonder: when will it end?”

The ravages of economic collapse and exploitation are also on display. We meet the unemployed children of former tobacco workers (the now all-but-disappeared tobacco industry once led the world), and learn of the vanished dairies, the faded rose perfume and silk enterprises, the last shepherd on the Turkish side of the boarder, the lighthouses now without keepers. The old orders are passing away, and the new ones bring little comfort. Since post-Communist Bulgaria’s free-fall collapse in the 1990s, slapdash development has despoiled the area in ways that remind Kassabova of the heedless damage being done to pristine parts of Scotland. We see up close how messy concrete plants and quarries and waste from the overbuilt fripperies of resort tourism threaten “one of Europe’s great wildernesses.” And we remember that the book’s dedication includes a “Plea for the Preservation of Forests.”

There are beautiful places on earth,” Kassabova tells us, “where no one is spared.” This deeply existential note is all too resonant in a time of climate change and global conflict. “What is the lesson of the story? Exactly, there is no lesson,” one acquaintance tells her. “Living here is like a joke without a punchline,” another says. Their fatalism recalls the book’s epigraph, in which the great Romany singer from Macedonia reminds us of the fundamentals:

“People forget that we are only guests on this earth, that we come on to it naked and depart with empty hands.”—Esma Redžepova

It all sounds pretty dark, right? But in fact the book sparkles with possibilities. There are other powers at work, human and superhuman. Here there is no clear line between past and present, individual story and collective myth. We visit a couple living by a waterfall at the cave where Orpheus is said to have descended into the underworld. We pass by caves on the Bulgarian side once used by Dionysian cults, and forests with megalithic cult sites left by Thracians back around 4,000 BCE.

Each chapter opens with a short prelude evoking a myth or cultural value. These themes anchor her encounters in a seabed of archetype: the power of healing springs (agiasma), the hospitality of roadside water fountains (cheshma), the belief in the world’s ongoing purifying struggle (agonia), and even the zmey, “a shape-shifting dragon that embodies protection and possession,” and “travels as a ball of fire, and can lead you through desire to the underworld.”

“To step across the line,” Kassabova writes, “ in sunshine or under cover of night, is fear and hope rolled into one.”

Literal belief in that fireball persists in these mountains where remoteness has spared old ways. In Bulgaria Kassabova witnesses firewalking, nestinarstvo, a legally banned ritual where fakir-like celebrants pass barefoot over hot coals to musical accompaniment. She finds it spellbinding, a powerful example of syncretic European culture shared by the Greeks, who call it anastenaria. “The whiff of paganism,” she says after attending, “was unmistakable under the burning incense of Orthodoxy.”

In Turkey, at today’s river border with Bulgaria, she learns of gatherings held for centuries among traditional pehlivani wrestlers and their communities “on both sides of the river, where women would fire the kurban feast, the sound of bagpipes and drums would echo from hill to hill, and potent home brews would be imbibed.” She also describes deep-rooted healing and fortune-telling practices such as reading the patterns made by molten lead from bullets when dropped into water. For people who share my interest in the folklore, music, and customs of the region, these descriptions provide a particular pleasure.

Above all it is the reach for beauty and healing in a fragmenting world that connects these stories with ours. While most readers may be gratefully spared the more desperate circumstances Border describes, we are also reminded that our time may be coming. Hearing that a national park in Bulgaria will become a dumping ground for new Black Sea resorts as “the stranglehold of big business and state interests tightened its grip,” Kassabova zooms out:

“I felt strongly that within my lifetime, we may all become exiles. That we may all be robbed by devouring daemons disguised as policy and industry, that we may all walk down some road carrying in plastic bags our memories of forests and mountains, clean rivers and village lanes.”

However dreadful this vision, the book ends in enchantment. The writer Maria Popova has shared the idea that some great writers are enchanters, who “go beyond the realm of knowledge and into the realm of wisdom,” working “toward a wholly different order of meaning.”

Call me enchanted. I came away charged with a sense of wonder and reaching for meaning. Kassabova inspired me with her boundless curiosity, the precision and sympathetic humor of her prose, her erudition and humility, and her atunement to the places and people of the border. Endlessly building on variously broken lives, they offer us renewal after all.

Anima, the fourth book in Kassabova’s tetralogy, is due out in August 2024. Stay tuned on Balkanography (or be in touch to write the entry!)

[1] For one of many discussions of Balkan Ghosts (and West’s limitations), see Marko Attila Hoare’s 2022 article in New Lines Magazine: ‘Ancient Ethnic Hatreds’ Is Poor Shorthand and Dangerous. Also, if you can find it, see my review of Balkan Ghosts from the time, “Portraits of Europe's Powder Keg.” New Leader 76, no. 8 (14 June 1993): 17-19.