“Everything it touched took absolute precedence for the simple reason that it was youthfulness, which seeks nothing per se, nothing but ‘everything’…” Tatjana Gromača in “Kraków”

May is springing full force these days, e.e. cumming’s “sweet spontaneous earth” answering winter with all those buds, blooms, and fiddleheads playing in the key of green.

The forward-driving month (its very name, May, granting permission for everything!) also sends me back, to my own sprouting, to the easy breath in my lungs and stride in my legs as I passed along a St. Louis sidewalk one day in May 1972, age 14, my world still opening like a tulip.

That afternoon a few treble notes drew my eye to the sloping roof of a brick two-story where a young woman in a white tank top and overalls (impossibly older, maybe 19) sat cross-legged over the porch playing a recorder. I was headed to the alternative radio station downtown, KDNA, thrilled to add my energy and complete lack of know-how to reinventing the airwaves, recombining the medium’s genome through scruffy listener-sponsorship, improvised antics, and random programming. I was late for my volunteer slot, but I stopped to listen.

This part of the Seventies was really the Sixties, and I had fallen under the madcap influence of Abbie Hoffman, Firesign Theater, and other pranksters. Yes, I marched to boycott lettuce and end the war, but among Marxists I mostly aligned with Groucho. The recorder player on the roof fit right in, and when I spotted her I knew in my cells and bones, for the nth time that week, that anything is possible and that remaking the world for the hell of it would be a joy.

Traces of that voltage may be why I responded so immediately to “Krakow,” by Tatjana Gromača in Take Six: Six Balkan Women Writers. In tracing her own path, she shows what it means to fall into belief, to fall out of it, and to forge new ways to love a battered world.

In her part of the anthology, Gromača captures her early years in five short sketches. Will Firth, the editor and translator, calls her works here travel prose, but beyond a series of finely drawn places, the journey takes us through moments in her life and in European history, through her wide-ranging associations and developing consciousness. We see, refracted through a well-seasoned lens, Gromača’s origins in the central Croatian town of Sisak; her first steps into adulthood in Zagreb; a student trip to Krakow, and a romantic interlude in Istria. Finally in Berlin in the 1990s, she finds herself seeking out other ex-Yugos, including other Balkan writers who were “mainly driven into exile by the exigencies of war and the merciless feebleminded ideology that stirred it up.”

She is no more a fan of Yugoslavia (“that odious and deleterious construct”) than of the “feebleminded” nationalist ideology that undid it, or of any ideology for that matter. In the selection “Kraków” she looks back more than 30 years to her visit to that beautiful city in the waning years of the Soviet Bloc. She recalls the promises embodied in the architecture—religious in the Wawel Cathedral, academic in the Jagellonian University, Europe’s second oldest, where stateliness turns out to be staleness (“churned-out quotes like broken old hurdy-gurdies”). She perceived, even then, the hollowness of such ideals when set against the grey scarcities of late-stage Communism and the barbarities of the Holocaust. “A mere glance at Poland’s quiet, peaceful, and harmonious landscape,” she recalls, “sufficed to imagine mass shootings in those meadows and fields.” Auschwitz was only an hour’s train ride away and a few decades back, and the farmers might well be hunting gold teeth left by Jewish victims in their lovely pastures.

But back then, Gromača tells us, she could still look to another revolution to solve what church, state, academia, and nationalism could not:

“I wanted to believe in a better tomorrow that comes in the form of a grand and old fashioned avant-garde and traditional revolution of the spirit—it would be made of the stuff of art, philosophy and literature, take the stage monumentally, and regenerate everything around it profoundly…”

Without condescending, the present-day Gromača underscores the darkness awaiting such bright hopes:

“Failure is a necessary by-product of living on an axis of veracity and peacemaking that does sometimes arise and sparkle as a shining example, a model to follow, but only if we’re advocates of unreality, of utopian, self-denying fanaticism. Otherwise in the vast majority of cases, such a life leads to being trampled underfoot, degraded, ridiculed and then dying for one’s principles, which the greatest part of humanity has forever turned its back on…

As if in illustration, she tells us that soon after she returned from Kraków, Yugoslavia broke apart in “a great bloody ruction, a Balkan danse macabre with a lot of mixed meat: Orthodox, Muslim, Catholic….” It was the most horrific conflict in Europe since the Second World War. “I came back to a ball of vampires,” she continues, “as if Poland had been a dress rehearsal, because what my imagination brushed there—the roamings of my inexperienced, naïve and still childish spirit—was actually happening here in real life, in physically reality…”

And yet, here she is, decades later, a writer of insight and delicacy capturing moments of natural beauty, human gesture, and sympathy that remind us, however uneasily, “that not everything is in vain, not everything is awry.”

Her first piece, “The Church of Mary Magdalene,” my favorite selection in the volume, illustrates that tangle of historical pain, love, and belonging. It brings us to central Croatia with a breathless description of the church itself and then a lovely tableaux of village life, with a shout out to Marc Chagall and his birthplace of Vitebsk in Belorus:

“This church and everything around it is most beautiful on a clear, bright snowy winter day. When the winter twilight gradually descends over the village and this whole sombre region along the River Sava; when on the road with a thin crust of ice the returning traveller sees a tipsy man on a bicycle, in a fur hat, leather coat and gumboots, trundling along on a rusty bicycle like a strange contraption from a prehistoric amusement park, at risk of being swept away by a speeding vehicle; and when the returning traveller also sees that cyclist with a load tied to the rack at the back—a sack of potatoes or, better still, a gas canister or a slaughtered suckling pig—then it suddenly feels as if someone has put a key in their hands to unlock the secret mythology of this region, a kind of Vitebsk, a historical transition zone with its own remarkable backwoods terms for everyday objects and concepts, and these have become the favourite words and give them a deep feeling of belonging to this obscure, dark ancestral homeland.”

How fond is that tipsy man on a strange contraption! How perfectly odd are his gas canister and suckling pig! He bikes along on ice, a Chaplin in fur hat and gumboots, hazarding the rush of modernity. But for all of our narrator’s intense sense of belonging to this passing world, she goes on to inoculate the reader (and herself) against sentimentality:

“an undefined sadness hangs over this whole region, over its poverty, subjection and cowardice, over the shame of who’ve become rich through plunder and theft—probably the melancholy of existence. Only occasionally does a spark of joie de vivre glimmer. Everything here is left, in complete fatalism to the will and actions of the gods, who never come or appear to finally take matters into their hands and see them through to a just conclusion.”

So there we have it—the gods are missing in action, and it’s really all up to us to shape a life of meaning. We are the ones who need to “finally take matters into their own hands and see them through.” Our hands might hold a brush, like Chagall’s, or a pen, or even a recorder on the roof. In the end, reading these essays I felt inspired by example and called to resist the deadening forces of maturity, which really, Gromača writes “is just a proud conceited term that serves to conceal resignation and fatigue, illness and defeat.”

It may be naïve, and blessedly so, to believe everything can change. But for better or for worse, it’s still our world to make.

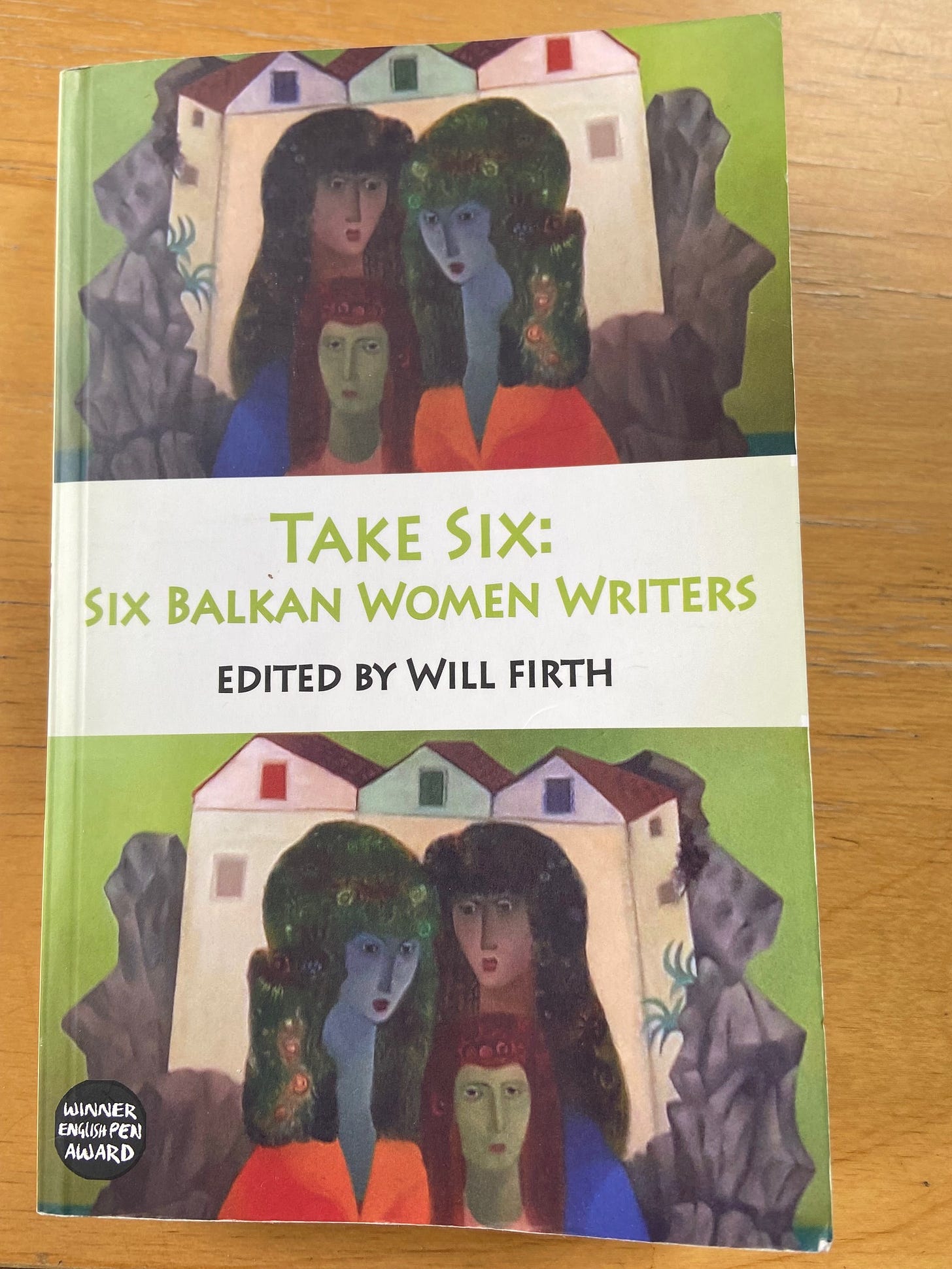

More about Take Six: Six Balkan Women Writers

The British publisher Dedalus books brought out Take Six: Six Balkan Women Writers in 2023, part of 10-year celebration of women’s literature. The other writers in the six-pack are Magdalena Blazević from Bosnia-Hercegovina; Vesna Perić (chief editor of the drama department at Radio Belgrade); Macedonian writer Natali Spasova, Ana Svetel, who writes in Slovenian; and Sonja Živaljecvic, now residing in Montenegro. Their works vary widely from the most starkly realistic to the most fantastical and fragmentary. You can get a sense of each and one reader’s response here at Lizzie’s Literary Life (Volume 2). Altogether, they issue an invitation to read more from each, and also to express a wish for more voices, to broadening the spotlight to those who write in the non-Slavic languages in the region.

About Tatjana Gromača

Gromača is an acclaimed poet, fiction writer, and journalist living in Istria. Her first collection of poems, Nešto nije u redu? (Something Wrong, Maybe?), came out in 2000. She wrote for the feisty Croatian opposition journal Feral Tribune and then for a leftist daily, Novi List. When she was fired from that job in 2016 she claimed it was “for her criticism of the nationalist point of view.” (No suprise, see above!)

Her award-winning 2012 novel, Božanska dječica, came out in English in 2021 (again, with Will Firth translating) asDivine Child. In the words of Ena Selimović, it

“tells the story of a woman diagnosed with bipolar disorder as Croatian politicians violently endorse nationalism in the 1990s. It asks how a community reestablishes what passes for “normal” when every social agreement previously made has crumbled.”

Read more of Selimović’s thoughtful review here, and hear directly from Firth on the challenges of the translation in an essay called "The Art of Anguish".

Just love this! The thoughtfulness and the writing both.

Beautiful Jerry! Thank you for sharing such words of deep insight and clarity through these women writers! I look forward to reading the essays.