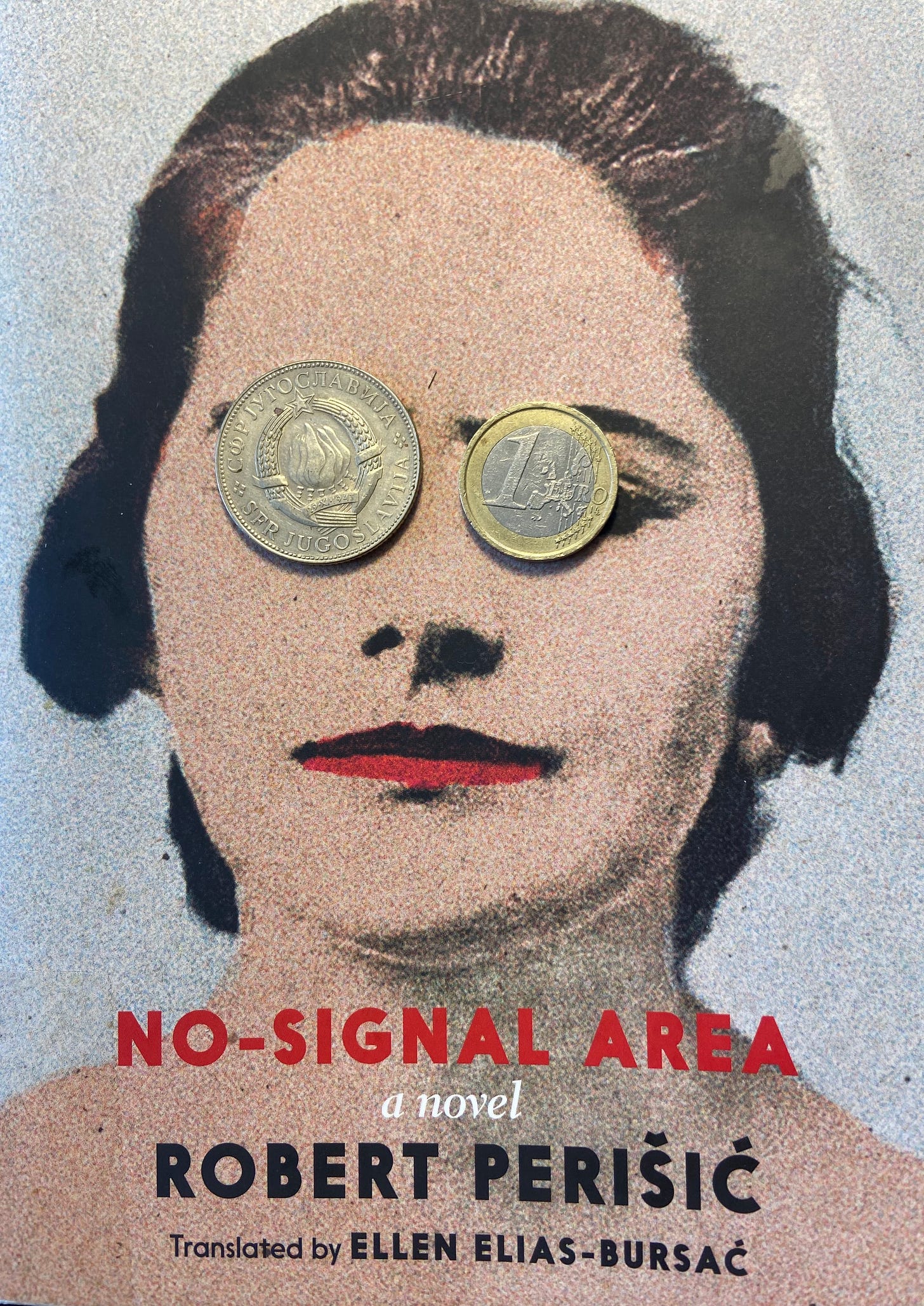

Here’s a Balkanographic thought: for page-turning storytelling, surprise, and ironic insight into people scrambling for meaning when systems collapse, go right out and get hold of No-Signal Area (Područje bez signala) by Robert Perišić.

Published in English translation1 in 2020 by Seven Stories Press, this 2015 novel by an acclaimed Croatian writer is a stunner. It’s driven by sharp dialogue, quick cuts in perspective and location, experimental voices (like whole chapters written by the town wanderer or his unhinged daughter), and imaginative sweep. And, beyond its glossy action-film surface, it is tender, rooted in careful characterization and the desires, fears, and stubborn hopes of people buffeted by change and loss.

It starts out like an Adriatic-style Ocean’s Eleven, as buddies Oleg and Nikola, urban “businessmen,” arrive in the shambling mountain town of N. N. is a faded backwater, up where Bogomils once thrived, historically barely worth the effort in the struggle between East and West once embodied in the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires and later in the three sides pitched against one another in the violent breakup of Yugoslavia. Here’s what Nikola sees:

“He walked along the cobblestone street where the two old empires had rubbed elbows, reluctantly, both as if they were losing momentum: they’d come this far, many miles from home, and were beginning to wonder what the point had been to all the adventure. There they stayed, forced by the other empire to dig in, and they’d been facing off ever since, centuries later, giving an inch now and then, a step here, a step there, bumping up against each other like two heavyweights staggering in a stranglehold, aching for the bell, almost cronies in their desperate exhaustion.”

Oleg and Nikola’s version of a heist is classic speculation: with no relevant experience, they will revive the dusty local turbine factory after 20 years, run it just long enough for payoff from a mysterious foreign client, cash in, and leave the town to die again. That’s textbook global extraction in the post-socialist Wild Wild East. As the plot, inevitably, thickens, it takes us into the heads of a wide cast of characters who retain other values, and out to Washington, Tbilisi, Vienna, Tunis, London, and beyond.

It’s all pretty cinematic. On a break from reading, I watched a glitzy dark comedy called Wolfs on Apple TV+, starring George Clooney and Brad Pitt (those Ocean’s Eleven guys). Afterwards, I couldn’t not see this book as a film, with those two cast as Oleg and Nikola. Then I learned that in fact there is an award-winning Croatian TV series based on the book with the (British) English title The Last Socialist Artefact. You can watch a trailer here on MUBI.

In N. and throughout the new global enterprises that feed on it, wires are crossed. Snail mail goes unread. Business relations teeter on the edge of robbery, romance on the edge of prostitution. Production has turned to scheming, fact into image (as one character says, “I’d begun to feel sorry for reality.”) Alcohol and cocaine numb brains and ease pains. The world of the novel is deeply awry.

“I’d begun to feel sorry for reality.”

Still, however strained, family ties, chances for love, and surprising heroism remain, seen most vigorously in the engineer Sobotka, a competent man who had been heartbroken at the cruelty of the war and the economic collapse of the 1990s. He and a younger worker, Erol, his appointed heir in running things, do good deeds and stay committed to the factory and the people around them, and they pay a price.

As in Divine Child, some of the most sympathetic folks are outliers, oddball survivors of trauma, like a truth-telling older filmmaker named Uncle Martin and the former factory worker Slavko. When we first meet Slavko, he is wandering the town with his dog, mumbling incomprehensibly. He eventually goes back to work, and in the end, shocked into action, he returns to the norms of shared language and logic he had rejected after the senseless death of his son. He only looks crazy in a world thrown so far off its axis.

This all gives us American readers a lot to think about in our time of swirling change and collapsing norms. So have a read and let me know what you think!

See you in December for a look at Anima: A Wild Pastoral. In her latest nonfiction book, Kapka Kassabova describes the efforts to hold on to threatened ways among the Karakachani (Sarakastani), traditionally seasonal migrants in southeastern Bulgaria and northern Greece.

Having finished reading this wonderful book, I'm struck by how well you capture the fullness and the nuance of it. Perišić, a man, inhabits the female characters with surprising believability but also creates male characters with great interiority and authenticity. None of these people are caricatures. They have their own individual struggles, ambivalences, internal dialogues, often painful histories and reflect the specific time, place, political context, and social trauma that formed and continues to shape them. Ultimately, there is a tender humanity that infuses all of it.