Time Shelter: Apocalypse Wow!

Georgi Gospodinov's Brilliant, Frightful Fantasy Has Its Consolations

“The time is coming when more and more people will want to hide in the cave of the past, to turn back. And not for happy reasons, by the way. We need to be ready with the bomb shelter of the past. Call it the time shelter if you will.” — Gaustine

Are nightmares for sharing?

Not if you were to ask Georgi Gospodinov’s grandmother. Back in the 1970s, when young Georgi started to relate a dream that haunted him, she cut him off: telling a dream, she warned, could bring it alive.

Gospodinov only kind of listened. Rather than telling, he wrote, creating (though he had barely mastered the alphabet) his first story. And in fact, as the acclaimed poet and novelist told a recent audience, the nightmare not only didn’t come true, it never came back.

Now a word about time: yours. If it’s limited and you haven’t yet read Time Shelter, maybe you should x out now and come back after you have. It’s that good. Also, you can hear directly from the author by checking out Time Shelter: Georgi Gospodinov with Valentina Izmirlieva | Conversations from the Cullman Center (that’s also where he tells about his grandmother and the dream). Their conversation starts about 13 minutes in.

If you’re still here, here goes.

Gospodinov’s third novel, winner of the 2023 International Booker Prize, explores the hold exerted over us by both memories of the past and anxieties about the future. The latter will be all too resonant for many readers—the curses of aging in 3D (decline, dementia, death); the atavism of tribal ethnopolitics; the dreadful end of days brought on by climate change, and other plagues. The novel explores in high-voltage, often hallucinatory, imaginings what can happen when fear of the future drives people to take shelter in the past.

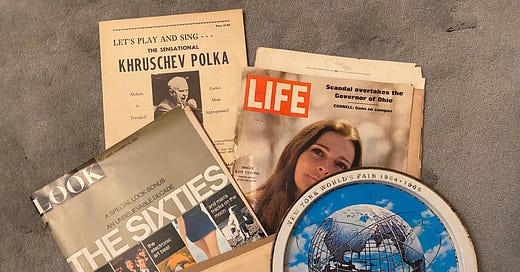

It all starts rather wholesomely as Gaustine, the narrator’s fictional alter-ego,1 creates “time clinics.” These physical spaces, rooms or whole floors, are meticulously designed to provoke memories in Alzheimer’s patients by matching sights, sounds, smells, and a thousand other details to earlier decades in their lives. The narrator, who shares Gospodinov’s name and biographical details, lends a hand by gathering patients’ stories. The logic of this therapy rings true to anyone who has said a long goodbye to a loved one with dementia—a mother, say, who doesn’t recognize her daughter but can sing along to all of An American in Paris. Soon, however (without giving away too much) patients’ families, then strangers, and then whole countries across Europe opt for the engineered comfort of a time shelter.

The narrator explains why:

“I suspect that some if not most of them did it out of nostalgia for the happiest years of their lives, while others did it out of fear that the world was irrevocably headed downhill and that the future was canceled. A strange anxiety hung in the air, you could catch a whiff of its faint scent when inhaling.”This longing for a sheltering past is understandable. It’s also dangerous, and the novel’s ability to alert us in various ways to the seductive spell of manipulated memories is all too germane for American readers today, as politicians and their media minions conjure a white Christian Golden Age to make America great again (yet again!).

Fortunately, Gospodinov’s early years vaccinated him against that kind of jive. He was born in communist-ruled Bulgaria in 1968, the year Soviet tanks rolled over the flowers of the Prague Spring. His characters recall the shabby deprivations and clumsy brutalities of the era, alongside its hollow triumphalist slogans. Though clearly fascinated by the everyday textures of the past and the personal memories they hold—the bite of a vintage cigarette, the weave of upholstery from the 1970s, the lure of old ads—our narrator warns us graphically against those who misuse our memories for power or profit.

As he focuses on one such manipulation—national chauvinism— Gospodinov’s native Bulgaria becomes the unfortunate target of his satire. Folkloric kitsch and clichéd versions of history comes squarely into his sights, from knock-offs of village costumes to the horo, the national dance, to Bulgaria’s trademark rose perfume, gajda (bagpipe), and any number of historical tropes, from the courage of the anti-Ottoman hajduk rebels to the tang of horsemeat jerky and kumis (fermented horse milk) tracing Bulgar heritage back to the Central Asia steppe. It turns out that even Šopska salata, that signature Bulgarian dish, is a recent construct, invented by an enterprising tourist official and matching the colors of the Bulgarian flag.

The critique of nationalism reaches a climax at a rally of “heroes” gathered to celebrate the past as a guide to Bulgaria’s future. A healthy crowd has gathered, clad in folk costumes (“with pistols tucked in their breeches”) and dancing a vast horo.2 A moment arrives when they look up in amazement to see

“A Bulgarian flag, carried by three hundred drones...flying in the heavens above us. The largest flag ever unfurled, a candidate for the Guinness Book of World Records.” (Here Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” would have fitted perfectly, though the organizers had chosen “Izlel e Delyo Haydutin” the Bulgarian song that had gone into space on Voyager instead.)”A young man is inspired to fire a gun into the air just like in the movies, and accidentally downs a drone. Copycat shooters follow his lead and a few more drones fall “like a goose shot in flight.” Then at once all the remaining drones open their pincers and drop the flag, shrouding all the would-be hajduks below. Only by using the daggers and sabers they carry in their waistbands do they escape suffocation. In none- too-subtle imagery Gospodinov takes on nationalism. He reminds us that despite its seeming authority, the nation-state is a recent contrivance, merely “a bawling historical infant masquerading as a biblical patriarch.”

Pithy pronouncements like that punctuate almost every page, as do allusions to a pantheon of European writers and artists. You could make a game of counting the references, whether to Thomas Mann, Walter Benjamin, Italo Calvino, Borges, Brodsky, or any number of others. The drone/flag/horo scene makes one of the more subtle leaps. “There was something strange about the whole sight,” we are told, “reminiscent of a post-apocalyptic film.” Reminiscent indeed! The whirling blades of the drones, the gunfire, the “Ride of the Valkyries,” all slyly evoke the harrowing scene of death from above in Francis Ford Coppola’s masterpiece Apocalypse Now. Wow!

Though published in 2020 (in Bulgarian), Time Shelter is very much a novel of the twentieth- century. It takes us time traveling through the past hundred-plus years (unstuck like Vonnegut’s shell-shocked Billy Pilgrim), to revisit signal moments that broke Europe again and again—Sarajevo in 1914, 1968, 1989. Even the cascading chaos that serves as the novel’s denouement creates a framework for encapsulating the century for various countries across Europe.

The book holds many eras, but one date hovers over it all: September 1, 1939, the day the Nazis invaded Poland. That day, the narrator tells us, “early in the morning came the end of human time.” What that means is not entirely clear, but we can surmise. That’s when any remaining illusion of enlightenment progress was wiped away, when Western civilization not only showed its discontents (as Freud wrote after WWI), but its complete bankruptcy, laying bare “the lie of Authority,” as W.H. Auden wrote in "September 1, 1939."

This all sounds pretty grim, blowing past dystopian to apocalyptic. And yet after finishing the book, I felt not only disturbed, but also warmed and reassured, even energized. How is that possible?

To venture an answer I will borrow from mindfulness meditation. The psychologist and mindfulness teacher Tara Brach coaches us to handle negative thoughts by allowing them, rather than shushing them like an anxious grandmother. She uses the acronym RAIN to suggest that in response we Recognize, Allow, Investigate, and Nurture. As we’ve seen, Time Shelter does plenty of the first three, But how does it manage to nurture?

First off, through an abiding tenderness—we feel it in the attention paid to patients’ stories, in the narrator’s memories of his own family, in his delight in language and ideas, and in his longing to belong. Late in the book amidst growing global chaos we get this vignette:

“Once, as a young man I found myself in a little square in Pisa, and since then I’ve known what the thing I’ve always wanted looks like…

It was one of those nights that you realize is not meant for sleep. You sink down into the unfamiliar streets. After a few blocks the noise has died away completely, Then you discover a piazza, with a little fountain and a church in the corner. And with a little group of friends, a few guys and girls, who have come out to shoot the breeze in the coolness around midnight. You sit down on a bench at the other end of the square, you listen to their voices, and if anyone had asked you at that moment what happiness is, you would point silently toward them. Growing old with your friends on a square like this, chattering and sipping your beer on warm nights, in a quadrangle of old buildings. Unperturbed by the lulls in the chatter, followed by waves of laughter, you don’t want anything more or less in the world, besides to preserve that rhythm of silence and laughter. In the inescapable nights of the coming years and old age.”

This idyllic scene celebrates the simple consolation of companionship, and —I’ll say it—love. (“We must love one another or die,” Auden’s poem declares in the face of the Nazi onslaught and corporate might.) We feel a sense of repose, a comforting settling into the present. That feeling stands in welcome contrast to a narrative that mostly flits between memory and dread, often making us feel like Blind Vaysa, a character described in the book whose one eye sees only the past, and other eye sees only the future.3

I also feel nurtured by the intelligence, scope, and precision of the storytelling. True, its springs bust loose sometimes in surprising directions, but the writing ticks along like a Swiss watch (or is it a time bomb?). Here a special nod goes to Angela Rodel, the translator, who deservedly shared the Booker Prize. The English is crisp, with lyrical passages that float, digressions that flow, and epigrams that punch (“Breaking news has long since broken,” to take one of a hundred examples). It’s hard to believe that phrases turned so tightly weren’t first crafted in English.

I’ll stipulate that art won’t save us from suffering. Still, however fraught our futures, hope abides in the human power to forge new meaning from mess. It may well be, as Tara Brach suggests and the six-year old Georgi seemed to already know, telling our fears, and playing them out, can rob them of their paralyzing power. And so though this masterful kaleidoscope of a novel takes us trippingly to the heart of darkness, it leaves us somehow heart-lightened and un-alone, like we’re in a circle of friends who understand us. Maybe in a piazza around midnight, lulled, at least for a little while, by the sparkle of the conversation and the rhythm of silence and laughter.

A character doubling the author as a kind of döppelganger is a device widely used by Borges and other modernists to explore the nature of the self and erase the boundaries between reality and imagination (Nabokov would put the word reality in quotation marks). Here the muddle it creates eases us into the plot’s speculative fantasy and helps us suspend disbelief. Gaustine, to the narator’s admiration and frustration, can get away with anything.

The song referred to below“Izlel ye Delyo Hajdutin” (“The hajduk Delyo Came Out”), performed by Valya Balkanska, did in fact leave our solar system aboard the Voyager spacecrafts. You can hear it and read more about Balkanska here. It was recorded in the 1960s by none other than Martin Koenig, Center for Traditional Music and Dance co-founder, and friend and inspiration to me and many Jerry’s Balkanography subscribers. The article includes his beautiful black-and-white portrait of Balkanska. I wonder what Martin would think of the associations to horo and the gajda shared in Time Shelter? Maybe one of us will find out….

Wow, Jerry ... Such a compassionate, profound reading of "Time Shelter". Beautifully written, too. Thank you!