Anima's Call of the Wild

Up with the sheep and shepherds, Kassabova leaves the degraded world behind

“A few pages are still left in the plundered green library of the earth. They are the only reading that feels urgent to me.” 1

In Anima: A Wild Pastoral Kapka Kassabova shares an urgent, sometimes rapturous, “reading” of a vanishing way of life. She delves into nomadic pastoralism, the seasonal flow of flocks and people toward good pasture, its practices preserved, for now, in the mountain reaches of western Bulgaria. Anima takes us high into the boonies and deep into the spirit of closely joined lives spent apart from the larger human world. Animals, their needs and whims, set the rhythm. The flock is the clock.

Pastoralism is holding on, through great effort, on the margins of modernity. (“I’ve always liked peripheries,” Kassabova said in a recent podcast. “A periphery is its own center if you really get to know it.”)

We do get to know it. The virtues of the endemic breeds of dogs, horses, and sheep. The details of hoof care, cheese-making, wolf and dog pack psychology, herbal remedies. The history of migration in the Balkans. And, all together, the inspiring dynamics of interdependence among all life forms up in the Pirin Mountains. As Kassabova learns,

“Mountain dogs, mountain sheep, mountain goats, and mountain horses go together, and human livelihoods and psyches have been woven into this web for thousands of years.”

The animals, ancient kinds spared from extinction, are the stars, right from the title on, as the epigraph explains: “Anima is soul in Latin. It is the root of the word animal—one with breath, soul, and life.”

Karakachan2 guard dogs lay particular claim to the author’s affections—we know their names, their faces, their temperaments, and how quickly a snuggle can turn into a snarl. We feel their fur. We also learn of Karakachan horses, small but legendary for agility along the ravines. As for Karakachan sheep, credibly thought the world’s oldest variety, the two flocks she encounters are but a remnant, a few wondrous drops from what was once a mighty sea. In the early 1900s more than half a million of their ancestors moved across the Balkans each year, watched by nomadic pastoralists—Karakachani, Vlachs, Roma, and others whose position outside of settled society always raised suspicion.3

Just to give a closer feeling, here is a lyrical video, posted on YouTube by Svetoslav Fichev, with some lovely images of herds, herders, and especially those Karakachan guard dogs.

Less happily, Kassabova highlights four catastrophes that befell nomadic pastoralism in the last century:

The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the Balkan Wars, and the drawing of national borders across traditional migratory routes in the early 20th century;

The Cold War hardening of those borders. As I’ve written, Kassabova’s Border vividly traces the ensuing traumas;

Collectivization in the 1950s, when the communist government in Bulgaria seized livestock. The Karakachani lost their animals and their freedom of movement;

Privatization and speculation after communism, the extractive capitalism at the center of Robert Perišić’s No Signal Zone.

Her other recent books cover some of this alienating history. But here, after a decade writing about Balkan peripheries and after months in near-monastic isolation from “the lower world,” she reaches a new level of estrangement. When she comes down off the mountain to town everything feels false, wasteful, pampered. Seeing 100 goat kids kept in a pen, she mourns their softened state in terms particularly unflattering to her own species:

“Fodder, the sedentary life, reliance on someone to bring you food, this is how enclosed animals become effortlessly fat but unable to survive in their native environments anymore, They become like humans.”

But we are not only lazy and ill-adept, we are also killers. The indifferent threat to nature posed by the industrialized world pervades the book. It is embodied dramatically in EU plans to run a highway right through Kresna Gorge, the heart of the region. The road would spell disaster for what is claimed to be the most biodiverse 17 km in Europe, and we meet the locals, including a biologist, who have fought it off. “The traffic along the good road was all one type,” we read, “big global business, a monocrop that threatened to gobble up the quirky mosaic on the ground.”

Life in the “quirky mosaic" is far from bucolic. It is unrelenting and rough-edged, sweetened by nature but soured by physical danger, isolation, alcohol and competition. True, the passion of her response can transport us when Kassabova loses herself (or finds herself?) in the stunning beauty and spirit of the highlands. But the characters she gets to know, Kàmen, Sàsho, Marina, and others, with their hard edges and hard words, keep the tone well away from sentimentality.

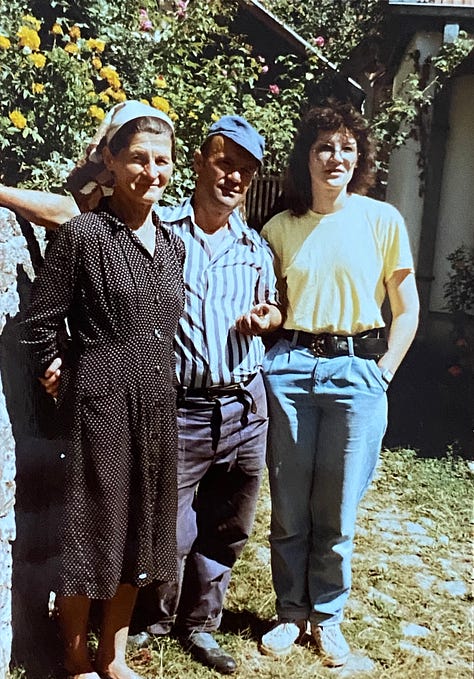

Those characters suspect they are the end of their line. Reading their reflections on the passing of pastoralism, and with it the DNA of a possibly better future, I thought back to my hosts on a farm in central Serbia in the 1980s. Their family had always been there on that hill, they told me, as far back as anybody knows. But this is the end: their daughter has gone from farmer to pharmacist. Together we all looked out over the wattle fences and haystacks and fields, where the cow grazed, took in the summer kitchen where the cheese is made, the backyard still for turning plums (40% of their acreage) into slivovica. A place out of time, in more than one sense.

I love how Kassabova’s books capture the twilight of old wisdom, the dimming light still shed in emptying villages in the Balkans where some remaining, often grandmothers, hold on to lessons forgotten in the cities. Lessons certainly in need of revival here in the industrialized United States, where long before I was born forces acting in the name of civilization had savaged the prairies, the bison, the forests and rivers, and the people who lived among them in a more sustaining balance.

In the beautiful Oscar-nominated Macedonian film Honeyland, the solitary beekeeper Hatidze Muratova holds onto her own balancing wisdom. Her new neighbors who pursue ruthless extraction, with disastrous consequences. But as she clambers over cliffs and gathers honey she holds back. It’s the same patience she shows in caring for her ailing mother. “We only take half,” she tells a young friend, “half for them, half for us.”

I imagine the herds and herders above Kresna Gorge, and their intrepid chronicler, would nod a saddened, emphatic yes.

The full quotation gives more context:

“The ‘book of wild men and animals’ is how a French historian in the early twentieth century described our pre-industrial planet. The book of wild men and animals once had innumerable volumes. Innumerable like the herds that crossed the land. “A few pages are still left in the plundered green library of the earth. They are the only reading that feels urgent to me.”

Named for the Karakachani nomads who kept them for centuries. See footnote 3.

The exact definition of these groups is confounding and the subject of much debate. I will cop out and quote the Wikipedia entry, with all due disclaimers:

“ The Sarakatsani (Greek: Σαρακατσάνοι, also written Karakachani, Bulgarian: каракачани) are an ethnic Greek population subgroup who were traditionally transhumant shepherds, native to Greece, with a smaller presence in neighbouring Bulgaria, southern Albania, and North Macedonia. Historically centered on the Pindus mountains and other mountain ranges in continental Greece, most Sarakatsani have abandoned the transhumant way of life and have been urbanised.”

They are often confused with Aromanians (Vlach), the other traditional large migrant group, whose speak a language similar to Romanian. The confusion is furthered because often all nomadic shepherds were referred to as Vlachs.

If you have more information on all this, please share!